How Nokia changed the world

Text: Richard Fisher

In the 1990s and early 2000s, millions of people around the world bought their first mobile phone. These devices were not smart. They didn’t have app stores or social media. But for the first time, they allowed us to speak on the move, send rudimentary texts, and play an infuriatingly addictive game called Snake. Their impact on the way we lived would be transformative.

For many people, that first phone was a Nokia. At the time, the Finnish company was a major player in the global handset market, making billion-dollar revenues, innovating in design, and even enjoying Hollywood cameos. In 1999, the "banana phone” that Keanu Reeves flipped open in The Matrix was a Nokia. Through modern eyes, the devices now seem basic – with text messages that read "gr8 2 cu" on pixelated screens – but for many people of a certain age, Nokia phones evoke pure nostalgia.

In Finland, Nokia provokes mixed emotions: there's pride and admiration that a homegrown firm was once the envy of the world, but also disappointment at its well-documented fall. In 2025, you can still buy a Nokia-branded phone, but the company itself no longer designs or manufactures them after it was muscled out by smartphone rivals.

Equipped with the benefit of hindsight, business consultants and journalists have since pored over Nokia's strategic mistakes. However, there's also much to learn about the period when Nokia was riding high. How did this Finnish company – thousands of miles from Silicon Valley – become a world leader in design and technology? And what are the lessons for firms aspiring to do the same today?

To find answers, researchers at Aalto University have created the Nokia Design Archive. Exploring the contents of the archive offers valuable insights into the culture in which its designers and engineers operated. But alongside these insights, we can also ask the people who were there: what's their perspective on why Nokia phones became so ubiquitous, and what was it like inside the firm in its heyday?

Rubber and rolls

Nokia's history goes back more than 150 years and for most of that time, the company was not known for its telephony innovations. In the mid-20th century, the rubber division of Nokia was making waterproof galoshes, boots and tyres, while the forestry wing manufactured toilet paper.

When Mikko Kosonen – former chair of the Aalto University board and former president of Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra – accepted a job there in the 1980s, his classmates teased him for joining such an uninspiring conglomerate. "It was a laughable thing for business students. Nobody wanted to go to Nokia because it was a boring company. They all wanted to go to other places those days."

Gradually, though, that reputation began to change, as Nokia repositioned itself as a world leader in telecoms. How did it do it?

Mikko KosonenFinland was a very savvy and very advanced telecom market.

"Finland was a very savvy and very advanced telecom market," explains Kosonen, who would eventually become Nokia's head of strategy and chief information officer. "Local circumstances and conditions have to be favourable for something new to grow."

However, the company's leadership also saw something about human behaviour that few at the time did: that phones would become a desirable object; a product that would appeal to teenagers and their grandparents alike.

Kosonen remembers a meeting in London in the early 90s where his colleague and friend Pekka Ala-Pietilä told an audience of investors that around a quarter of the world would own a mobile phone by the year 2000. "He was not taken seriously. Nobody believed that it could be possible," he recalls. "Everybody in those days still thought that this was a device that only professionals needed – police or other officials – not consumers. There was no such thing as a 'mobile phone' market. Nokia made the market."

Armed with this foresight, Nokia reorganised itself internally into two different businesses – infrastructure and handsets. "At the time, everybody else saw them as one business," says Kosonen. That meant they could focus on designing phones that people coveted. "Nokia invested early in brand and design," he says. "It was the 'wow' effect with Nokia phones."

So, in little over a decade, the "boring conglomerate" that Kosonen joined in the 1980s – making toilet roll and rubber cables – had positioned itself to design objects that would appear in Hollywood movies, celebrity paparazzi photos, and the hands of catwalk models.

Nokia's ability to pivot its business is a trait that current company leaders might learn from, says Kosonen. After leaving Nokia, he studied the renewal strategies of global companies. Nokia was one of several case studies that he and his collaborator Yves Doz analysed in a book ‘Fast Strategy'. They argued that a successful board has "strategic agility": a sensitivity to new opportunities, an open-minded commitment to change, and the resource fluidity to move fast.

At the turn of the century, Nokia's products were making the company billions, and Nokia alone accounted for 4% of Finland's GDP. Its spirit of creativity and optimism would shape the nation’s self-identity for many years, giving Finns self-belief as its success helped pull Finland from a bitter recession in the 90s.

'Disneyland for designers'

One young designer who was drawn by the "Nokia Way" was Tej Chauhan, who now runs his own design firm. After joining the UK office in 2000, he would go on to create various models, including the "mango" and "lipstick" phones. Compared with today's ubiquitous black-rectangle smartphones, these models were highly unusual – and capture the creativity and freedom of Nokia's company culture at the time.

One day, a member of Nokia's management team came over to Chauhan and asked him: "Do you want to design something crazy?" The mango phone was the result, marketed as a "souvenir from the future".

"It was like Disneyland for designers," Chauhan recalls. "I was surrounded by lots of brilliant people. It felt like being part of a family."

"There was a very proactive creative spirit," he adds. "If you wanted to go and research, say, a phone made out of banana skins, there's a good chance that you might get some budget to go and do that, so long as you could tie it back to a business goal."

With the mango phone, for instance, it wasn't just its unusual shape that was innovative; Chauhan also wanted consumers to be able to customise it with leather or textile clip-on parts. To work, this required an entirely new injection-moulding technology, and prompted "a bunch of head-scratching" from the engineers, he says. But it worked, and he has the patents to show for it.

A piece of history

Both Chauhan and Kosonen are happy that the Nokia Design Archive is being preserved and studied at Aalto University. "Nokia is not just a part of Finnish design history. It's part of modern Finnish culture," says Chauhan.

Kosonen feels that the university is a natural home for the archive, because many of Nokia's engineers and business leaders (including himself) are alum from the technical, creative and business schools that united to create it. As an institution, it also embraces the same innovative and collaborative culture that defined Nokia, he says.

Above all, the archive gives us a precious opportunity to look back at a pivotal point in history, from another pivotal point in history.

If we had known back then where technology would take us, would Nokia people have made the same decisions? And are today’s big tech innovators smart enough to learn from the past as they make choices that shape our future?

As ever, knowledge is power. Like Neo in the Matrix, perhaps the lessons from a past tech giant can help us dodge some future bullets.

***

Nokia Design Archive has been made possible by donations from Microsoft Mobile Oy and designers and by funding from The Research Council of Finland and the Kaute Foundation.

Nokia Design Archive

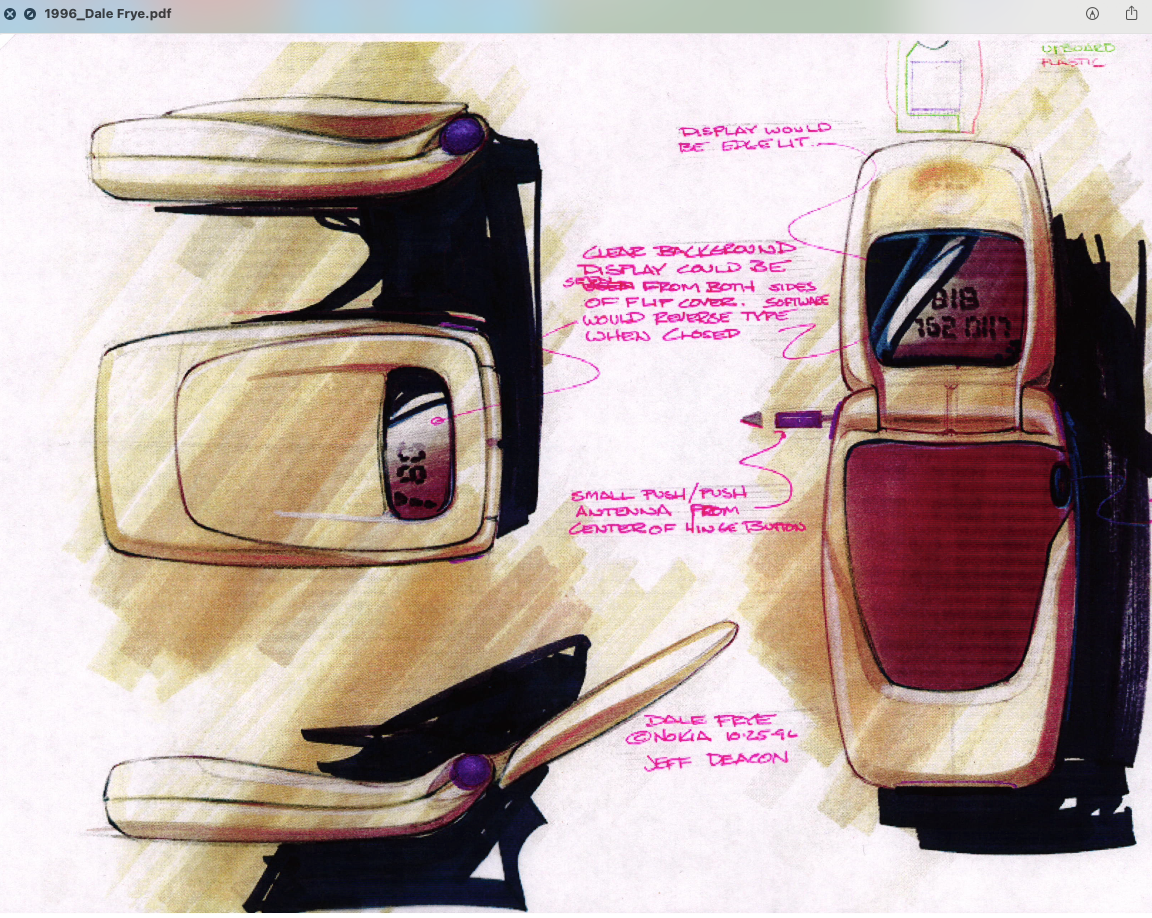

Opening the door to two decades of Nokia’s history, this online portal features never-before-seen material, from the raw ideas behind iconic designs to eye-opening concepts that never left the drawing board.

“Left outside in the rain”: The story behind the stories of the Nokia Design Archive

In a strange twist of fate, a team of Aalto University researchers found themselves responsible for two decades of Nokia’s best kept design secrets.

The visions that shaped us: Nokia Design Archive opens to the public online

Opening the door to two decades of Nokia’s inner workings, a new online portal brings never-before-seen material to the public.

Read more news

Training available in AI, research data management, research ethics + more – register now!

New topics included! Registrations for spring 2026 are open.

New Innovation Postdoc programme launching this spring in Aalto

Innovation Postdoc launching this spring for AI researchers eager to turn cutting-edge research into real-world impact.

Expansive frontiers: tracing wilderness

Expansive Frontiers: Tracing Wilderness is a research project developed over a period of three months by doctoral researcher Ana Ribeiro, during her time as a Visiting Researcher in the Empirica Research Group at Aalto University